BILLINGS — Research that compared Yellowstone National Park grizzly bear and wolf interactions with those same animals in Sweden has produced a surprising finding: brown bear presence in both ecosystems reduces the wolf kill rate.

“It’s a baffling finding,” said Doug Smith, Yellowstone’s wolf biologist. “To be honest, for 20 years I’ve been saying bears increase wolf kill rates because bears steal so many carcasses.”

That data from two very different ecosystems pointed to the same conclusion helped convince Yellowstone bear biologist Kerry Gunther that the research was “not just a fluke.”

The study’s lead author was Aimee Tallian, a Utah State University wildlife ecologist and former Yellowstone research assistant. Eleven international co-authors helped with the National Science Foundation-funded project that allowed Tallian to spend a year working in Sweden.

Different worlds

The research area in south-central Sweden is very different from Yellowstone, Tallian noted. Roads criss-cross the dense forest because it is logged. That means researchers could drive to most locations, compared to Yellowstone where hours spent hiking is more often the norm.

“It’s heavily managed by humans, but there are still a lot of woods and remote areas,” she said.

Yellowstone is also unusual in that grizzly-wolf interactions are sometimes seen along the main roads where they are photographed by tourists or studied through spotting scopes. Seeing the animals in Sweden is rare, partly because they are still hunted populations.

Research says

Tallian said the assumption that the presence of an apex predator like grizzlies would drive wolves to hunt and kill more prey was never written down anywhere, but was a commonly held belief.

“The results were the opposite of what we expected,” she said. “I double-checked the data so many times thinking, ‘What did I do wrong?’”

“Our results challenge the conventional view that brown bears do not affect the distribution, survival or reproduction of wolves,” stated the research paper, which was published in the “Proceedings of the Royal Society B” on Feb. 8.

“Although the outcome of interactions between bears and wolves at carcasses varies, bears often dominate, limiting wolves’ access to food,” the paper said. “Furthermore, our findings suggest that wolves do not hunt more often to compensate for the loss of food to brown bears. In combination, this implies that bears might negatively affect the food intake of wolves,” so wolf populations that live within the same geographical area as brown bears may see effects on their fitness.

King of the kill

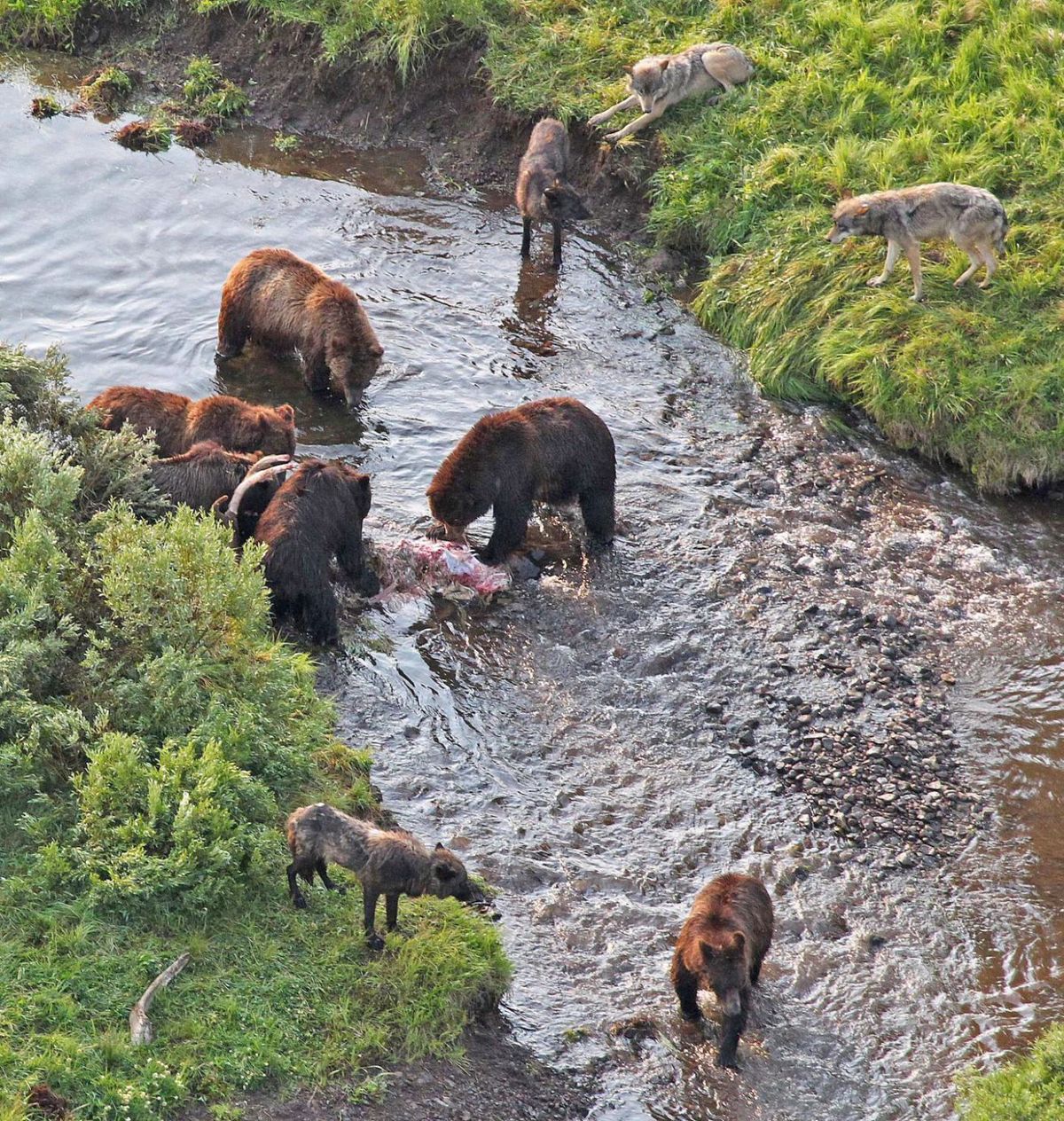

Past research by Smith and his crew in Yellowstone’s remote, bear-rich Pelican Valley have found that, between March and October, virtually every wolf kill is taken over by a grizzly bear.

“Wolves get a lot of food stolen from them by grizzlies,” Smith said.

Gunther said it is common in Yellowstone for grizzlies to usurp wolf kills within hours, if not days. Takeovers by females with cubs is less common because the wolves will threaten, and sometimes kill, the young bears.

“The missing piece was: What does that do to wolf kill rates?” Smith noted.

Tallian said many assume that wolves are efficient and effective killers. But previous research in Yellowstone has shown that summer is a lean season, the same time that grizzlies are out of hibernation competing for food and there’s no snow to slow down the wolf’s favorite prey, ungulates like elk. Faced with a food shortage, packs break up into smaller groups with wolves often dining on smaller and more varied prey than in winter.

Source: Carcass-stealing by grizzlies doesn’t mean wolves kill more | Montana & Regional | missoulian.com