JACKSON HOLE, WY – Last summer Roger Dobson, and Patricia Herman, a tribal spokesman for advocacy group Protect the Wolves, spent two months in Yellowstone observing and videotaping 911M, an old pepper-gray wolf with sparkling eyes. He watched the blacktail alpha male of the Junction Butte pack uncharacteristically introduce another male into his pack to breed with the females.

Dobson/ Herman observed him watch his pack with the wisdom of an old sage. Later that year, after a valiant fight and several injuries, Prospect Peak wolves killed 911M.

After three wolves from the pack were harvested in late 2016, and another disappeared, the Junction Butte pack was only seen sporadically and it was difficult to identify its wolves.

Dobson says a turning point for him as an activist was when he videotaped outfitters riding right by the den where the Junction Butte pack lived in Yellowstone. “They were within 75 feet of the den, which is illegal, and their horses were loose, but they didn’t receive a ticket or get banned,” he said. A district park ranger called them 30 times, and Dobson asserts, “they saw the missed calls but claimed their phone never rang.” He believes this is what drove the pack out of the area to create another den, which had a negative impact on the size and health of the pack.

“It’s disgusting,” Dobson said, “what people—ranchers and hunters—get away with.” He said a lot of Native Americans believe in protecting wolves but don’t want to be outspoken or ruffle feathers. But a true activist, he said, doesn’t sugar coat the issues or compromise integrity by allowing rich outfitters to get away with disturbing a wolf sanctuary. When they’re “in bed” with the local politicians and ranchers who have donated to advocacy groups that play “both sides of the fence,” then prominent wolf experts support management plans that put ranchers ahead of wildlife and treat wolves like “pests.”

Dobson said Protect The Wolves has received more than 100 death threats, but it doesn’t bother them. He told one caller, “We’ll just meet in the woods and handle this the old Indian way,” and never heard from him again.

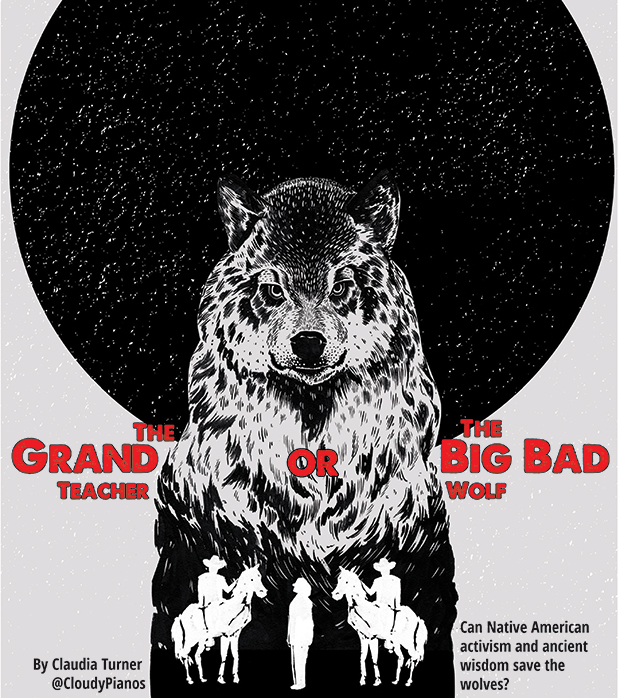

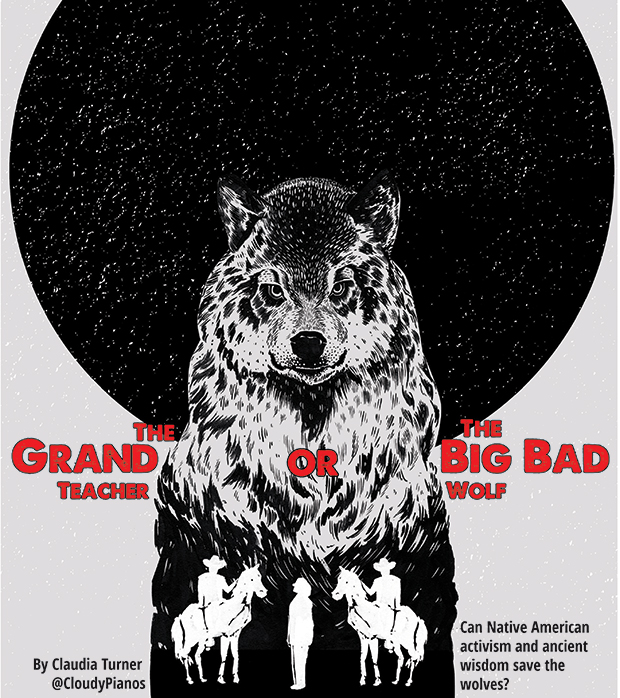

Native American traditions depict the wolf as a “grand teacher” and sage who returns after many years upon a sacred path to relay knowledge and wisdom to the tribe. Their sacredness is extolled by people who study the natural world. “The gaze of the wolf reaches into your soul,” wrote naturalist and author Barry Lopez.

Indeed, wolves are important in the history of almost all Native American tribes. They are considered closely related to humans, and loyal to their packs and mate. In Shoshone mythology, the wolf plays the role of the noble creator. Some tribes have wolf clans, and there are wolf dances, totem poles with wolf carvings, and clan crests for tribes of the Northwest Coast, such as the Tlingit and Tsimshian.

In contrast, Western folklore has a different outlook with stories like Little Red Riding Hood and The Big Bad Wolf and the Three Little Pigs. American idioms, too, illustrate a notion counter to what Native Americans believe: “Throw you to the wolves”; “A wolf in sheep’s clothing”; and Don’t “put one’s head in the wolf’s mouth.”

In Native American teaching, the wolf embodies wisdom, courage and faith. The material world is comprised of relentless sorrows and difficulties, and to overcome them one must trust in a higher spirit. The wolf is a symbol of that spirit on earth, as is the grizzly and the owl. But Western ideology tends to separate the human spirit from the earth and its creatures. It is a dichotomy that has fueled the debate about who gets control of what land and who has the right to hunt what animal.

Sacred space

Take a trip to Ravendale, California, and you’ll find a population of 36 and a lot of backcountry. There’s also Dobson/ Herman and their ranch. In May, the 40-acre ranch two hours north of Reno was purchased as a future sanctuary for gray wolves. The tribal advocacy group has members across the country, but now its roots are in Ravendale, headed by , and Dobson, president of the Protect the Wolves Pack, and his partner Patricia Herman, president of Protect the Wolves Sanctuary. They’re in the process of registering the group Protect The Wolves Pack as a 501c4, a social welfare organization. Dobson, an ex-Marine and member of the Washington State Cowlitz Tribe, said the advocacy group’s primary focus is protecting wolves and all the animals considered “sacred” to Native American tribes.

In Idaho and Montana alone, hundreds of gray wolves were slaughtered and maimed in traps during hunting season, and hunters and trappers have killed more than 4,000 gray wolves in the lower 48 states since 2011. Protect The Wolves™ vision is to protect sacred animals but also educate the masses on the importance of protecting wildlife and their natural habitat.

But can the masses grasp the idea that something wild could be precious and something precious could be—with one minor change—on the verge of destruction? Dobson follows the Native American Religious Treaty Rights. They seek to ban hunting, and make poisoning wildlife illegal across North America and ban hounding and traps. They also aim to institute policies to use all non-lethal practices to manage wolves and coyotes.

While Protect the Wolves™ has no staff in the Greater Yellowstone Region, it does have volunteers in Wyoming, along with tribal endorsements throughout North America. The Eastern Shoshone and Northern Arapaho Tribes are still evaluating the proposal to make a buffer zone, while Protect the Wolves is working to build protections in Idaho and Montana as well. Dobson says that ranchers and government officials, who make decisions with rancher mentality: “Cattle are good, and wolves are bad,” rule these areas. Basically, he says “sacred” is not in their vocabulary when it comes to wildlife. It’s this ethos activists in and out of the tribes want to change to reshape the dialogue behind gray wolf management planning.

Protect the Wolves has been up against governors, senators, ranchers,one example was the “Crying Cowboy” at the September 2016 meeting in Washington State, that Patricia carried out a box of Kleenex for…. hunters and businessmen, and a lot of people don’t like mixing Native American traditions with advocacy groups. “It’s the typical 1800s rancher mentality. … Most Ranchers everywhere are the worst, there are a few that others should pattern themselves after. They all have the same typical mentality: shoot, shovel, and shut up,” Dobson said. “Leave your Indian stuff at home,” is what they are silently expressing, he said. It’s a constant tug-of-war between what people want and what’s right.

“I can network better by picking up the telephone and calling people.” And, indeed, he calls everybody—the head of the National Park Service, members of Wyoming Game and Fish, Governor Matt Mead’s office, Sen. Mike Enzi’s office, heads of the Northern Arapaho and Western Shoshone Tribes. But he believes the consensus among people is “don’t rock the boat.”

Sergio Maldonado is a committee member on the business council of the Northern Arapaho Tribe, and state liaison for Mead, though his liaison duties will end this month due to budget cuts. He stressed he cannot speak on behalf of the tribe or Mead. But his opinion is that wolves have a place in the ecosystem and should be respected. He is concerned Wyoming Game and Fish, and others involved in the decision-making process, do not see wolves as “sacred” in a society where “man has dominion over all things,” and a history of radically affecting the ecosystem on an international level. The effects of which are more visible every day.

“On a genetic level [the wolves] haven’t forgotten their treatment by man, and they keep their distance,” Maldonado said. He hopes that the wolves’ contribution to the ecosystem and their sacredness to the tribes will be taken into consideration when Wyoming implements its final management plan.

A meeting will be held on July 17 with the Department of Justice, including wolf experts, Wyoming Game and Fish, wolf biologist Doug Smith, Dobson, and Maldonado. A proposed buffer zone and other management planning of wolves will be discussed.

“I would suggest that we as a society fully reconsider our ideas about all living beings on this planet, as well as the environment, as our time here is fragile and this earth doesn’t need human beings. This sacred earth will continue on without us,” Maldonado said.

Protect the Wolves’ proposed buffer zone would restrict wolf hunting in a 31-mile stretch in Yellowstone from the border of northwest Wyoming to southwest Montana. Critics of the plan argue it betrays the public trust. Proponents, meanwhile, say the public trust betrays the “sacred” rights of tribes, not to mention basic science and the belief that hunting will negatively impact not only the population of the wolves but also the ecosystem. Dobson noted that “sacred” is often a term frowned upon by all sides for its emphasis on tribal beliefs.

The buffer zone request sent to Game and Fish seeks temporary suspension of wolf hunting altogether, along with the 31-mile “sacred resources protection safety zone,” near the outskirts of Yellowstones 2.2-million acres. When asked about this proposed zone, Renny MacKay, communications director for Wyoming Game and Fish, stressed the need to first review public comment.

Likewise, Enzi merely said wolves have been an issue “Wyoming has had to contend with ever since the federal government excised to reintroduce them to the state.” He said that everyone from Wyoming governors, state legislatures, federal government and stakeholders have worked hard to create a wolf management plan for Wyoming and that “the bottom line is that Wyoming should be in charge of Wyoming’s wildlife.”

The war on wolves

When Yellowstone National Park was created in 1872, the gray wolf populations were already in decline in Montana, Wyoming and Idaho. The creation of America’s first national park did nothing to protect the wolves and government predator control programs in the first decades of the 1900s essentially helped eliminate the gray wolf from Yellowstone. The last wolves were killed in Yellowstone in 1926.

Not until the 1940s did park managers, biologists, conservationists and environmentalists begin the foundation of a campaign to reintroduce the gray wolf in Yellowstone. When the Endangered Species Act of 1973 was passed, legal reintroduction was on the way, and in 1995, gray wolves were first reintroduced into Yellowstone in the Lamar Valley.

Reintroducing wolves is infinitely more dangerous than preserving them. In 1995, eight gray wolves were brought by truck from Jasper National Park in Alberta, Canada, to Yellowstone. The population has since grown to an estimated 100 wolves. Since the reintroduction, wolves have kept the elk populations down, which in turn keep their damage on forests down, which allows aspen and willow to thrive. Meanwhile, beaver populations have increased, dam production has returned to normal, and river patterns have improved. Thanks to the return of the wolves to Yellowstone, and contrary to the myths of the Big Bad Wolf and the critiques of the GOP and ranchers, equilibrium has indeed returned to the Yellowstone ecosystem.

“Yellowstone is the best place in the world to view wolves,” said Smith, project leader of the Yellowstone Wolf Restoration Project. Today there are about 60,000 gray wolves living in Alaska and Canada, 3,500 gray wolves in the Great Lakes, and an estimated 1,700 in the Western states of Montana, Idaho, Wyoming, Oregon and Washington.

On April 26, the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service delivered a final rule to comply with a court order that reinstated the removal of federal protections for the gray wolf in Wyoming under the Environmental Species Act.

A 2016 BBC article by Niki Rust references studies in which culling (selective hunting) was allowed in the United States. Culling was used to eliminate wolves suspected of attacking livestock or that were perceived as threats to human safety, even though there has never been a record of a person attacked by a wild wolf in either Wisconsin or Michigan. The study showed that wolf populations continued to grow unless culling was allowed, and then populations slowed by one-third. Therefore, the idea that “allowing hunting will increase tolerance and consequently decrease poaching” is “one of the most widespread assumptions in large carnivore management,“ said Jose Vicente Lopez-Bao, PhD, a conservation biologist from La Universidad de Oviedo in Spain.

Adrian Treves, PhD, associate professor of the Nelson Institute for Environmental Studies at University of Wisconsin- Madison, offered a possible explanation. “If poachers see the government killing a protected species, they may say to themselves, ‘Well I can do that too,’” he said.

Treves, a Harvard graduate in human evolutionary biology, began studying wolves in 1999 and 2000, when a pile of data on wolves was thrown onto his desk for analysis. He read hunter and rancher complaints, participated in focus groups, and ecological and biological data on the wolves. The Carnivore Coexistence Lab was founded in 2007, to study large predator animals like big cats, bears and wolves, and their interactions with humans.

There have been two essential takes from nearly 20 years of research. First, managers aren’t following peoples’ actual tolerance when hunting is legalized or liberalized. Research shows that when hunting is liberalized, poaching increases and political calls to increase hunting rise. Second, poaching—the primary cause of mortality—has been misidentified or incorrectly measured.

Traditional methods make two errors: simple algebraic errors and errors in estimation when scientists and government agents underestimate the effects of poaching. Radio collaring is the typical proactive method for following the “known fate” of a wolf’s life and death. But every study has shown marked animals are consistently lost, and managers and scientists traditionally assumed that these missing radio-collared wolves’ fates were the same as known fates.

Algebra errors come from assuming causes of death are the same in unknown fates as known fates, because legal killing should be reported but none of the unknown fates are legal kills. To assume unknown fates are the same as known is simply false, Treves said. “Managers and scientists in the past who reported poaching never asked what had happened to unknown fates.”

Some possibilities are death by natural causes and illegal killing. Treves studied all four endangered wolf populations, including the population in the northern Rockies, and found legal killing had been over-estimated while poaching had been under-estimated by wide margins.

In 2010, Smith, who was studying Yellowstone’s restored predators, published a mortality pattern that said legal killing was the major cause of death in the wolf populations. Reexamining the math, Treves found that poaching was in fact the primary cause of death for the entire wolf population, “when we properly included the unknown fates” legal death fell to a third.

So what happens when conservationists don’t identity the worst threat to a species? “By misidentifying the major cause of death for Northern Rockies wolves, they didn’t intervene against the real worst threat,” Treves said. Imagine police officers patrolling the streets for shoplifters when looting is the real problem.

Managers have great control over the fate of the wolves, and often they just aren’t paying attention. There’s an “institution inertia,” and new scientific documentation takes time to be considered. Neither a tribal advocate, a spokesman for the U.S. National Park Service, nor a Wyoming Game and Fish rep were aware of this study or interested in talking about it. When poaching is the worst threat, and the government response is to allow legalizing and liberalizing wolf-killing, history suggests this will not only increase poaching but also worsen public opinion and the attitudes of politicians in relation to these animals.

There are, just in recent years, several cases of illegal hunting of wolves and grizzlies in and around Yellowstone. On April 11, a popular 12-year-old white wolf was found illegally shot within the park grounds just outside of Gardiner, Montana. She was mortally injured and officials were forced to euthanize her. Jonathan Shafer, who works in Yellowstone National Park’s office of public affairs, says the park has not taken a position on the proposed buffer zone, but it is strongly opposed to poaching and wants to take every step necessary to find the hunters. Recently park officials announced they would offer a $25,000 reward for a tip that leads to the arrest and conviction of the person(s) responsible for illegally shooting the wolf.

While an official motive hasn’t been released, many advocacy groups believe without a doubt that opponents of wolves in Yellowstone, primarily ranchers and hunters, are to blame. This is just one of several cases where ranchers and hunters have acted out their dislike of wolves returning to Yellowstone. In 2012, the park’s most popular wolf, 832F or “06 Female,” was shot dead by a hunter.

Seven men and a plan

Wolf hunting isn’t allowed in the Trophy Game Management Area (TGMA), where most Wyoming wolves live, and there is not an established hunting season in place. Wyoming Game and Fish says it will use the current wolf population, biologist input, and public comment to develop new hunt area quotas and a draft hunting regulation. The public comment period on Chapter 47, “Gray Wolf Hunting Seasons” closed last week.

Game and Fish’s MacKay said there is a recommendation on how to regulate wolves now that they are no longer on the Endangered Species Act. This recommendation is based on biologists and scientific studies and is structured on the goal of both protecting wolves and providing sport for hunters.

Advocates like Protect the Wolves would like to keep all wolf hunting banned. But MacKay says they need to hear from everyone, and there are several advocacy groups, and thousands of comments from ranchers, government officials, hunters and general citizens to consider. July 19 or 20 will be the deciding day, when a seven-member commission (appointed by Mead, each member with a six-year term) will review the comments on wolf regulations, and make a final decision on how to manage the current population in Wyoming.

Every year the department has a monitoring and management report for gray wolves as well as monthly updates on their conditions. Game and Fish maintains approximately 413,000 acres of land, including nearly 225 miles of streams and more than 148 miles of road rights-of-way.

MacKay noted Game and Fish has managed wolves in the past, and that he was proud of the work it had done. It work he was “honored to do.”

However, advocates like Dobson remain wary. He says he doesn’t trust Game and Fish because it has called wolves “vermin” and that it completely ignores and bypasses the “sacred” rights of the tribes. He’s concerned when wolf experts and managers want to distinguish the life of a sacred being because of money, and says that there are special interests behind the scenes that disregard nature and disregard the spirit.

As stated by Delice Calcote, executive director for the Alaska Inter-Tribal Council, “Tribal Nations and peoples believe that we are connected to the wildlife, to the plant life, to the lifeways in the waterways and airways. Our ancient historical creation stories and legends, and spiritual beliefs include the important role that the wolf has here on our Earth Mother.” PJH

Source: FEATURE: The Grand Teacher or The Big Bad Wolf – Planet Jackson Hole